A chat with some our French team

Who are you? And how did you become involved in Just Scapes?

Cécile

I’m Cécile. I’m a researcher, a social scientist in geography, and I’m working on social interactions at the interface between agriculture and the environment; and on collaboration and conflicts at landscape scale. I’m supervising the French team for Just Scapes. And I've worked a lot in the Pyrénées before on conflicts between livestock farming and biodiversity conservation, and how these things are negotiated locally.

Lisa

I’m Lisa. I finished my masters last year, and did my end-of-studies internship with Cécile and Floriane in Just Scapes, conducting the first-round of interviews and analysing them. And now I’m continuing for Just Scapes on a short-term contract.

Benjamin

And I'm Benjamin. I come from a master’s degree in ecology, with a specialisation in social sciences. In Just Scapes I’m managing the creation of the participative workshop and I’m really interested in the analysis of the individual interviews, so I try to do both. I also grew up in the Pyrénées.

Why this valley?

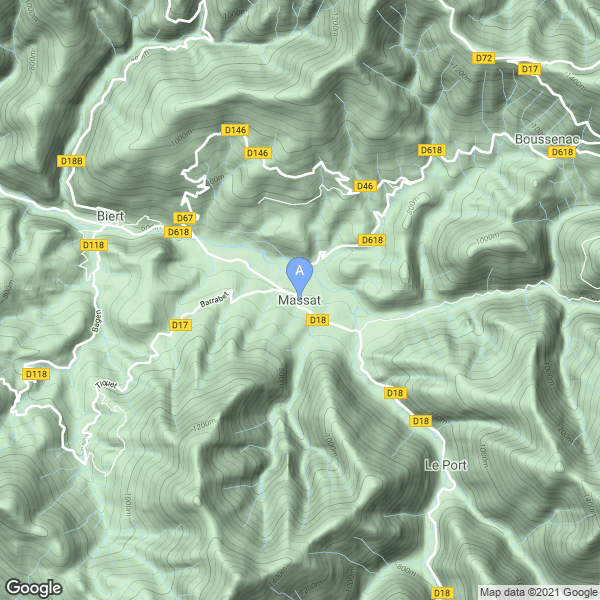

What was the reason for choosing the Arac valley for our case study?

Cécile

So the choice of the initial partner, the National Park of the Pyrénées Ariegeoises was the first reason why we chose this part of the Pyrénées. They had already thought about climate transition, which is quite rare. So they’d already done what they call a “plan paysage” (landscape plan) on climate and energy transition.

Then we discussed which place to choose – which study area From our side, we wanted to make sure that we chose a place where traditional livestock farming was present and supported. In the Pyrénées in general, there’s often consensus about the need to maintain livestock farming to maintain open landscapes. Spontaneous reforestation is seen as bad for both landscapes and farming – leading to loss of culture, patrimonial landscapes, biodiversity and productive landscapes for farming. But then you have climate change discourse, which says that growing forest is good and that livestock farming is bad for the climate. Our initial question was: “Will climate change discourse impact this existing local consensus on livestock farming?” And so I wanted to have a place where this consensus existed.

We needed a place quite high up in the mountains and initially we also wanted to have a place where we could talk about wood and forest management, too. There are interesting questions about how to manage forests in terms of climate: some people recommend using wood for energy, others say to use if for construction. There’s also the question of whether it’s good to cut down trees in terms of carbon storage.

So that’s how the Arac valley came up. And we found out that it’s a very specific valley because, since the 1970s a lot of “hippies” came to the area to try alternative lifestyles – having their own land and growing vegetables for their families. And it’s still attracting many of these newcomers, or “neo-rurals”, as we call them. But even if now there aren’t so many traditional livestock farmers in number, they still manage the majority of the land there.

Our question, on whether or not climate change is destabilising this consensus on livestock farming is very live here. People do talk about it and take it seriously – creating tensions. So it’s an interesting place to think about how to address these new concerns – but also about trying to find balance and compromise, and to creatively imagine what kind of future these mountains could have.

Cécile BarnaudJust Scapes French team lead

Benjamin: you grew up in the area but not in this valley, right? So what was your understanding of this area? Did you know something about the area beforehand?

Benjamin

No, no, not at all! I’d only been there maybe two times in my life before. So I learnt new things every day. And I didn’t know the agriculture topic very well either, so I learned about it in the valley and by reading papers. For me it’s great because everything is linked, and as we talk about agriculture we also talk about land more generally, and food, too.

Let's talk landscape...

People who are reading this maybe have never been to this area. What do you see when you visit the Arac valley?

Lisa

At the bottom of the valley there are a lot of fields where their livestock farmers will be able to cut the grass in the summer and use that to feed the animals in the winter. And in the intermediary zones – the steepest zones – there are a lot of woods. These are the zones that have been abandoned by agriculture over the last few decades, because it’s very difficult to bring machines there and so the woods have grown spontaneously. Some of the forests are exploited, so you can see some of the rows of trees that have been planted and that will be cut. But it’s not the majority – most of it is just spontaneous reforestation.

And then at the very top of the mountains you can many “estives” (summer grazing pastures), where the shepherds will keep their animals from around June to November, giving time for the livestock farmers to cut the grass in the fields at the bottom of the valley. So the animals will graze freely all throughout the summer on the top of the mountains, and come back down to go inside in the fall.

Cécile

I’d just add that, compared to other valleys in the Pyrénées, Arac is quite woody. The other valleys often have more open meadows, open fields.

The research so far...

Where are we in the process so far? I understand you've done some initial interviews and some workshops?

Lisa

In May and June we spoke to 25 people. This included a few livestock farmers; some vegetable farmers; some locally elected people; a few people who lived in the area and didn't necessarily have a job linked to land-use; and people who worked in the forest domain.

And then Benjamin and I did quite a few interviews prior to the workshop – the same type of interviews; I'd say we modified a few questions. We were trying to get at the diversity of visions that exist in the valley and to use this to prepare the workshop.

And for the interviews you've done so far, what’s been as you expected and what's been surprising to you?

Lisa

That’s a good question! I guess when I when I first arrived, it was sort of all new to me. So I was discovering a lot about the basic dynamics that exist there. And it’s been really interesting to be able to continue the process one more time with Benjamin, because I feel like now we can ask different types of questions. Even though I knew when we arrived that there were a lot of neo-rural people, I didn’t expect them to have so many different projects, or such a strong dynamic of trying to find alternative ways of life.

Cécile

Well, I’d done many interviews and similar projects in the Pyrénées before. And, as I said earlier, livestock farming there is seen as good for the land and for biodiversity. It’s the pillar of these valleys. And to suggest that there might be other kinds of biodiversity, and that it might not be fair to pour all these subsidies into livestock farming was very much a taboo – something that people wouldn’t dare say out loud, or on the record. In this valley, I was very surprised because people do say it. They don’t say it right away, but it’s quite strong and I was surprised at that – “Wow, that’s not a taboo here!”

And it’s not that, as a project, we want to question livestock farming – that’s not what we’re doing here. But it’s interesting to hear local voices that do question it, because in cities people do. It’s also very much linked to the question of reintroducing the bear in the area, which is highly divisive –if you’re not against the bear, that means you’re pro-bear. And if you’re pro-bear, you’re a serious enemy of livestock farming. It’s a subject that comes up again and again. It’s very interesting in terms of representations of human-nature relations. But we don’t want to bring it up in the workshops, because it’s so contentious that we won’t be able to foster any dialogue then.

Benjamin

From my side, I’d say that we clearly have a lot of conflict about access to land but also, paradoxically, a lot of people – and diverse people – who want to help each other and to find a way to live in solidarity. There’s a range of stakeholders who’d like to mutualise working land.

I was surprised to see that – even with these different conflicts – we still have some people who are ready to give a piece of land and try to work with people who are different to them. I was happy to see that!

Benjamin Begou Research collaborator, Just Scapes French team

So there are some unexpected possibilities or new spaces opening up then?

Benjamin

Yes. And possibilities for dialogue.

Cécile

I have one more surprise, actually. Usually in the Pyrénées we talk a lot about rural exodus and decline of land use. But here there are people who want to do something with the land. As in other places, you have conflict over access to the “good lands” (the flat lands that are okay for mechanisation), but here it seems to be even more of an issue. And that’s why people are talking about using the “bad lands”; the ones that have been abandoned and reforested because they’re too steep. So that’s the kind of thing that we’ll discuss in the process.

Speaking of dialogue

You just ran the first of two participatory workshops (“T-labs”). How did it go? And what were you hoping to get from this part of the research process?

Lisa

The first workshop was partly about presenting back the early results that we had from the study: our interview findings and Marie’s work, who did her master’s thesis on agrarian systems in the area. The idea was to show people what we’d done and get their feedback. The second part of the workshop was about getting at local preoccupations and issues.

Benjamin

When we designed the workshop, we tried to find a way of making these issues emerge, but we also tried to find a way to do something that could be useful for the participants, too. In the end we had 30 participants (a lot!), so it was sometimes difficult to manage the different stages, but in the end I think it was interesting both for us and for them.

Unfortunately we didn’t have a lot of livestock farmers – we tried to get them to come but maybe it wasn’t good timing for them. So in the next few days, Lisa and I will try to interview them individually, to go through a similar process and get their input.

Cécile

We had neo-rural farmers there, but not the traditional livestock farmers. But we did have some institutions that represent traditional livestock farmers, so at least their voices were somehow a bit present.

Benjamin

We also had a lot of vegetable farmers, an environmental non-profit organisation and other local institutions. Plus some involved citizens and elected people from the local government (municipalities).

Lisa

We also had someone who works for the ONF (the public organisation that manages national forests in France).

Benjamin

And that helped us to reconnect forests to the issues about agriculture, too. We had a lot of participants who were involved in a collective concerned with food autonomy/ sovereignty, so they talked a lot about the difficulty in accessing land and about finding more balanced land use, with more space for vegetable producers.

Lisa

This question of autonomy is very interesting in the project. A lot of people in the area really would like to get to some level of food autonomy, even though the scale isn’t clear. But there's also another question about the autonomy of livestock farms. They often can’t produce enough grass to feed their animals, and so need to buy food for them.

There’s also this question not only about land use but of what autonomy are we seeking? On what scale? And I think people have very different ideas of what they put behind that word.

Lisa DarmetResearch collaborator, Just Scapes French team

Perhaps creating a framework for dialogue through the workshop process is already something?

Benjamin

Yes, for sure. And I think the next question will be: “Can we re-use the existing tools to facilitate better collective access/use of land?” Or how could we create a new, needed tool? And there’s also the question: “Which project we want to do together?” How do the participants want to work better collectively? These are likely to be things we talk about in the next workshops.

Lisa

And it comes back to what Cécile was saying: it’s not that easy because some people have more interest in keeping the status quo. And we didn’t hear so much from those people yet, so we still need to make space for their visions.

What's next?

Okay, so you’re one workshop down. What’s next in the research process?

Benjamin

Next Lisa and I will do some more interviews: both with some people who were in the workshop, to get their feedback on the process, and also with some traditional livestock farmers who couldn’t attend. And the next step will be the creative-writing workshop in June.

PhotosLandscape photos: © Marie Izard. Vegetable farming photo: © Lisa Darmet. Workshop photos: © Jérôme Prudent.