A chat with David Brown on our Scottish case study

Who are you? And how did you become involved in Just Scapes?

I'm David Brown. I’m based in the UK and my research background’s in environmental and climate justice. I look at the justice dimensions of climate-change transitions and how we can mitigate against negative social aspects of different kinds of climate action. And I’m particularly focused on rural areas.

For this project I was very keen to explore some of the justice barriers to climate action and transformations in rural areas in Scotland, and how different perceptions of justice and different values influence people’s responses to climate-change policies and actions. And how these cut across different social groups and interact with social inequalities/power relations.

Why this area?

So why did we choose Highland Scotland for Just Scapes?

Scotland's an interesting case, with net-zero commitments and climate-change targets for 2045 being set by the Scottish Government. So it’s interesting to look at the implications that these targets will have for the very large rural areas in Scotland and how they’ll change rural land-use there. Climate-change responses might include enhancing carbon capture, increasing biodiversity and/or carbon sequestration. There have also been many emerging rewilding initiatives in Scotland over the last few years. They emerged separately from climate-change policies but are now becoming intertwined with them.

So I guess there's some distinctive elements of the Just Scapes project. We're asking how rewilding relates to the climate-change agenda and these net-zero commitments in Scotland. We're trying to understand the social dimensions of landscape restoration in the context of climate action in rural Scotland. And we’re using an empirical justice framework.

We’re looking at how these kinds of potential changes in rural areas in response to climate action might have particular justice implications. What are local people’s underlying values and ideas of justice? What are their perceptions, experiences and understandings of the landscape and landscape change? What underpins some of the social conflicts around landscape restoration and rewilding?

"We’re looking at distributional, procedural and recognitional justice. What kinds of community benefits might there be? Do the community have a voice that gets heard? Land ownership and land inequalities are a key part of these questions in the Scottish context."

David BrownResearcher on the Just Scapes UK teamLet's talk landscape...

What's the Highland landscape like, and why are words like “carbon sequestration”, “biodiversity” and “rewilding” relevant there?

Well, it's largely a mountainous landscape. But it's also one which has been degraded over recent centuries: partly by agricultural activities but also by deer hunting. These kinds of activities have led to deforestation and degraded peatlands. And natural restoration processes have also been prevented because of the deer numbers.

Planting trees and restoring peatlands have been earmarked as key ways in which we can sequester carbon, improve biodiversity and respond to climate change. And some of the rewilding projects in the area are very much focused on native tree planting as well.

So deer control and tree restoration are key to landscape change. And this creates a conflict between climate-change action and some of the activities which have been dominant in the area over the last couple of centuries: primarily these large-scale sporting estates, which are often owned by wealthy private individuals.

The Scottish Forestry Commission have been planting trees since WW2, as a response deforestation but also to sell wood. So these commercial plantations are also a key part of this landscape and are now being harvested, so are reaching the natural end of their life cycle. In the last couple of decades, the Forestry Commission’s strategy has changed: they're starting to plant more mixed woodlands and include more native trees.

Rewilding projects are also looking to develop these native woodlands. And in many cases, this will actually involve cutting down some of the non-native woodlands and replacing them. There’s also an argument that native woodlands are better for carbon sequestration as well: partly because they won't be harvested, so will act as a longer-term carbon store.

The research so far...

And where are at with the research process? You’ve done some interviews, right?

Well, first we surveyed the current literature base on rural environmental justice to see what the state of play is, and where our research fits within this space. And we can clearly see that there's a gap in looking at links between rural environmental justice and climate change.

But yes, the first part of our fieldwork has involved carrying out preliminary in-depth interviews. We interviewed 22 people in September and October 2021. The idea was to interview a range of different stakeholders in our case-study area.

(Corresponding to the "Affric Highlands" defined by Trees for Life, covering over 2,000 square kilometres and including Glens Cannich, Affric, Moriston and Shiel.)

This included landowners from traditional sporting estates but also newer investors who are more interested in green investments and rewilding/restoration. These so-called “green Lairds” have invested in land in recent years in response to increases in carbon financing.

We also interviewed NGOs, including Trees for Life; as well as community groups and different community stakeholders, including those who look after funds in the local area. And we interviewed an environmental manager at the National Trust.

The idea was to get a get a sense of how people thought about climate change, what they thought were the current local issues, where they thought opportunities might be in relation to land-use change, and where they saw potential conflicts.

The expected and the unexpected...

You conducted the initial interviews. Did anything come up that surprised you?

Land reform

We knew that land inequality is a big issue in Scotland. There are questions about whether a just transformation of landscape in the Highlands should include “land reform” – radical shifts in land ownership/management – or whether it can operate more or less within the status quo (i.e. incentivising land owners to adopt more sustainable management techniques, to plant trees, to restore peatlands, that kind of thing).

But one of the things I didn’t know before the interviews was the extent of small-scale alternative models of land ownership/managed that have emerged in recent years. Some are social enterprises but there are community woodland projects as well.

I guess in the last in the last 20 years land ownership in Scotland has diversified a little bit, even though it's still fundamentally dominated by the large-scale individual landowners. But the Scottish Government have committed to increasing the diversity of land ownership with the 2003 Land Reform Act, which introduced community right to buy. And there was the 2015 Community Empowerment Act as well, which looks at empowering community bodies through land ownership and strengthening their voices in decision-making. There’s also a government target of increasing the total land area in community ownership to 1 million acres.

There’s still a way to go though. Another thing that came out through the interviews was how limited the capacities of many community and volunteer networks are – many of these community woodlands are maintained by volunteers and there’s only so much people can do.

"So the land question underpinned a lot of the discussions we had. And it raises questions: if not land reform, what other kinds of land governance models are possible?"

David BrownResearcher on the Just Scapes UK team

There’s been talk about collaborative partnership governance models, which means land ownership might not change but these models imagine how different stakeholders, including communities, could work together on a new vision and different kinds of land management.

Species reintroduction

This was another hot topic – particularly about reintroducing the lynx and the wolf. And it’s often the first thing people think of when they think of rewilding.

NGOs like Trees for Life are not putting species reintroduction at the centre for the moment – they’re focussing on re-establishing natural habitats. But this issue does dominate local conversations around rewilding. Opinions on species reintroduction don’t cut cleanly across different social groups: there are tendencies, but it's more a bit more complex in reality.

Some people see the benefits of reintroducing the lynx for example, as they see it as restoring the natural food chain of the landscape and helping to control deer numbers. However there are also many fears amongst local people that reintroducing predators may pose a threat to humans and pets, and that it may affect farming livelihoods too.

People/re-peopling

And another key theme and justice issue was around the role of people in rewilding. A lot of the local community voices we heard raised concerns about the inclusion of people in rewilding developments, which we expected. But I wasn’t expecting how long a shadow is cast by the Highland Clearances, which fed into a sense of injustice and mistrust of externally-driven interventions. This means that, for many local people, the words “wilderness” and “rewilding” don't have a very positive resonance.

"Many local people are understandably concerned about the idea of a wilderness without people. And for them the landscape is profoundly cultural and has been co-created by human and nonhuman processes together."

David BrownResearcher on the Just Scapes UK team

So for many locals the rewilding agenda should be closely linked to the re-peopling agenda, which responds to the injustices of the Highland Clearances, and a broader backdrop of rural depopulation post WW2 and particularly in the last couple of decades. This has been driven by loss of decent employment opportunities; rising costs of land, housing and living; and an increase in second-home ownership.

There were also mixed views among local people on the potential of rewilding. On the one hand, they hope that eco-tourism developments could create new job opportunities in nature-based businesses, instigate rural economic development and encourage people to stay in the area. But these projects are also likely to lead to higher numbers of visitors, which may strain the infrastructure of rural communities or lead to even more second homes. There were also concerns around access. In Scotland you have the right to roam, but people were worried that – as has happened in other areas in Europe – rewilding might create enclosed spaces that you have to pay to enter.

So there's that broader question: will rewilding put people at its centre? Will it respond to these social justice issues? Or will it just perpetuate community decline further?

Community benefits and voice

And then I guess the final point might be around what the role of community is going to be in these projects. Even though Trees for Life and other rewilding NGOs are increasingly talking about the role of people and community building, it’s still quite unclear what this would mean in practice and how a rewilding-based rural economy would work.

"It’s also unclear what kind of community benefits would come out of this. Because, of course, there’s a key social justice issue about who benefits from this potential for carbon finance. With the existing land inequality it means that the financial rewards from restoration and carbon sequestration are currently likely to be captured by a small number of private landowners."

David BrownResearcher on the Just Scapes UK team

What alternatives could there be? Will they be tied to land ownership or could there be some kind of community-benefit mechanism there, as happened with renewables? (Windfarm and hydropower levies have been a big driver of funds for different community projects in Scotland in recent years, although many locals still have mixed views about these developments.)

So there’s a question around whether carbon funds will follow the same sort of path and, if so, whether communities will have more of a voice in how carbon-capture projects are developed. Will they be included in, or shut off from, decision making?

What's next?

Super interesting start! So what’s next for the Scottish case?

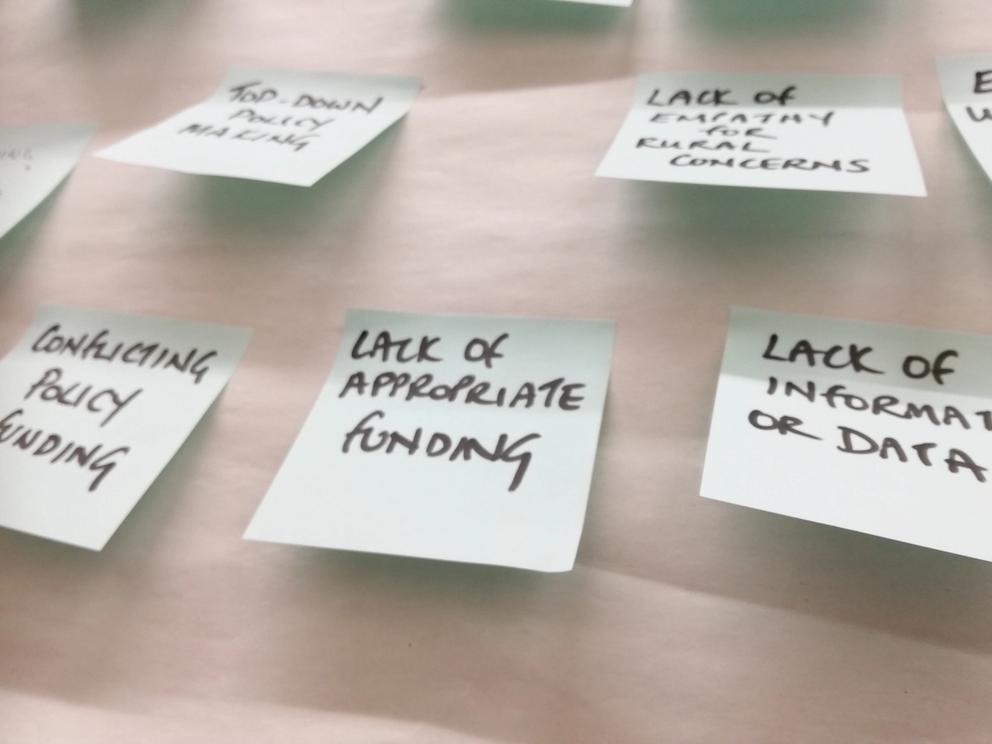

We’re going to carry out some deliberative workshops with local people, again trying to include a range of local stakeholders to establish a working group on landscape transformation in the case-study area. We’re running our first “Transformation-lab” at the beginning of May before doing a second workshop in June.

At the workshop, we want to work through some key issues that came up in our interviews. We’re ultimately working towards establishing a common vision for sustainable land use in rural Scotland, and a picture of what just and sustainable transformation in the context of climate change could look like. We’d like to create a manifesto from this process, to feedback to relevant stakeholders, like NGOs and different government bodies.

And then later, in June, we’re running a creative-writing workshop. Again, we’re looking at inviting a real diversity of stakeholders to better understand local people’s sense and history of the landscape.