A chat with some of our Czech team

Who are you? And how did you become involved in Just Scapes?

Zuzana

I'm a researcher who has been dealing mostly with future scenarios and pathways to sustainability. I got into this project because I had previously collaborated with the PI, Adrian, for an IPBES assessment that was looking at the role of values in how we govern nature and the sustainability issues around us.

And because we were working on the connection between values that we hold as people and future development, we kind of found ourselves on the same page – Adrian more from the environmental-justice perspective and I came from the futures perspective. And then when the chance came up to collaborate looking at environmental-justice issues related to climate, that was a match.

Barbora

I deal with environmental issues that are more connected to conservation efforts and their impact on human societies. But I saw a call that Czechglobe was searching for a researcher to help them with this project and I was really interested in the topic because I think that cultural factors, forestry issues – all these things are really important in the Czech Republic. And I also found it interesting that there were other national case studies.

And since I'm a cultural anthropologist, I thought that it might be quite interesting to see the cultural issues and attitudes of other people on this particular issue. So I applied for it and they picked me. So that's how I ended up on Just Scapes!

Why this area?

Why did we choose South Moravia for Just Scapes?

Zuzana

Because Just Scapes is dealing with rural areas, we wanted to work in a landscape that would tick a few boxes. One of them was that we wanted to work in area whose problems would be somehow relevant for a larger proportion of the country. And that’s why we wanted an agricultural landscape. And we also wanted to work in an area that was already somehow actively thinking about change, because we wanted to be able to connect to activities or projects that were already happening. So, at least from my side, I was interested in having something that's representative of issues that people are dealing with across the country and at the same time ongoing active local engagement in tackling these problems.

Let's talk landscape...

And what what is this landscape like? What do you see when you visit South Moravia?

Barbora

I think it's a very beautiful part of the country, even though the more I am involved in this project, the more I see how tragic it is, too. That’s because the landscape is a combination of really large, vast agricultural plots and you can see many problems with the soil there, such as erosion and all these other things. But at the same time there’s countryside where, even nowadays, you can still see more traditional pieces of farmland, which are really tiny. And people still grow their own grapes there, which is not something that you see just anywhere in the Czech Republic.

"I think that those binaries are a dominant feature of this part of the country: they’re really striking."

Barbora NohlováDoctoral researcher, Just Scapes Czech team

I think it looks rather depressing in the winter and early spring, but in summer and in autumn, it's all green and it looks like France or something! So yes, I like to go there because I find the countryside very lovely!

Zuzana

I totally agree. I guess I would add that the landscape is a rural landscape. It’s full of villages that are quite close to each other, but are still quite small. But what might be contradictory to a similar landscape in western Europe is that in South Moravia there are very few small-scale farms, due to how the landscape has been developed, historically. Most farms that you can see are actually large-scale, highly mechanized farms. So that means that the landscape is mostly full of larger plots of land and what makes it special is just exactly what Bára said: that there are quite a lot of vineyards here.

The research so far...

You started by doing some interviews. How did they go? Who did you speak to?

Barbora

We started by interviewing our NGO project partners here in the Czech Republic, and they recommended we speak to one particularly interesting person: a farmer and NGO member. He had some very long interviews with us – the first two took about 6 hours because we started to chat! (He had lots of time because it took place before the farming season started.) It was him who introduced us to these five villages: he was our gatekeeper. We started by speaking with the village mayors. Then things started to snowball because the mayors were interested in the project: they wanted to know more, and recommended more people to speak to.

There have been two phases of the interviews. For the initial “interview” we just told them about the project and answered their questions – so the conversations were rather short. And then we arranged a second, longer interview. I think that this phase was important for us because we wanted to understand whether these people and these particular villages would be interesting for us as researchers: whether there were any issues there that we needed to or wanted to look closer at. And at the same time, we also wanted to check if the people we spoke to were really engaged, and if they really wanted to work with us. And of course we also wanted to tell them something about us.

So, first off, we created some kind of relationship of trust, let's say, and then in second phase we did the research interviews, in which we asked about the village, about the landscape, and what kind of problems they might be experiencing there.

At that time we were still in lockdown in Czech Republic, so the first part was online. Then for the second phase we went to the field and met people face to face. But whoever we spoke to, the structure of the interviews stayed the same: we always asked them about the landscape and life in the village. And they also took us through the countryside to show it to us.

Speaking of dialogue...

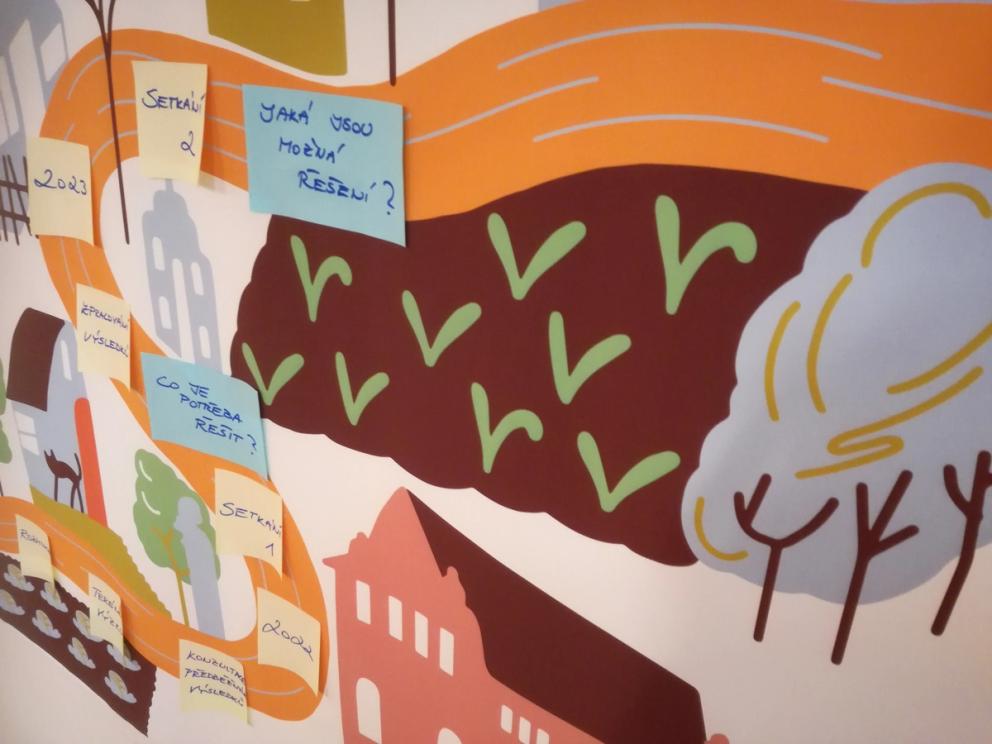

You've also been running a participatory workshop that we're calling “T Lab” (“transformation lab”). And you've run it in several different places so far, right?

Zuzana

I think what we always feel like when doing participatory work is that we’re asking people for their time and for their energy and for an investment from their side. And it feels like you would like to balance that investment by showing that you're also trying to bring something to the process. And I think that, this time, for us, it boiled down to really trying to reach people where they live. We really wanted to try to make it as easy as possible for them to take part, if they were interested in doing so, and to lower the barriers to participation. So we decided that we would like to take the workshop to them, by travelling across the different places where people live in the municipalities that we are working with. This meant that we repeated the format several times so that people could join really in their home environment. Their place.

"We were trying to bring it as close to people as possible. And then also it turned out that it's quite interesting to do the same design repetitively across the municipalities, because you see different dynamics and different opinions. So it was very interesting!"

Zuzana HarmáčkováTeam lead, Just Scapes Czech team

And what about people’s input? What has been as you expected? And what’s been surprising?

Barbora

I think that what happened as I expected, were the issues that came up – because I’d already spent some time with these people at this point. So I was delighted that the same themes were emerging over and over again.

On the other hand, I was quite surprised that some of those issues stopped, at some point in the process, to be quite so urgent. For example, at the beginning quite a lot of our participants complained about the agricultural subsidies and how they’re unjust.

"But in the process the legislation actually changed, and we realized that it's actually not such a burning issue for them anymore, because most of our participants were smaller farmers. If we’d had more of the huge agricultural players participating, the picture would be different and I imagine they’d be quite outraged because it wasn't a favourable legislative change for them. But it was a fair change. So that was a good surprise in a way!"

Barbora NohlováDoctoral researcher, Just Scapes Czech team

Zuzana

For me it mostly boils down to seeing how we think about change in different places. And I think for me this is one of the biggest differences… You know, if I take away the formal system and ecosystem/economic setting across Europe and just look at the way people perceive change, I think there’s a fundamental difference between different European populations.

"In the areas that we are working with, people are mostly craving balance and stability. Change is not a topic that would be sexy or interesting for people. That's one thing that I found really important."

Zuzana HarmáčkováTeam lead, Just Scapes Czech team

And the second finding was that I think there might be difference whether people prefer to think about change as something that should be instigated from the top down or from the bottom up: where people see their place in change. And I think in the Czech context, people very much see change as something that should be happening top down. Then we’re wondering where to see our role within that change. I thought that was very interesting and something that kept emerging quite frequently.

What's next?

These are issues we'll continue to explore over the rest of the process. So what's next for the Czech case?

Zuzana

Well, when we were talking to the stakeholders it was quite apparent that people would like to see some kind of mechanism that would make it meaningful that they’ve invested their time in sharing their insights. They’d like to see a mechanism that turns the research into something practical. And because a lot of the barriers that they have been talking about have been top-down barriers, I think our next logical next step is to now spend some time disseminating our intermediate findings to different ministries and authorities; to places which do hold some kind of power and to see what the reaction is. That will mean that we have something to bring back to our case-study area in the next stage.

And based on that, we’d like to work on thinking about change and planning for change a little bit more in the final part of the project. But, once again, I think that's something that we will have to fine-tune to fit with the theory of change that the local people have in their minds.

Barbora

And we also have the Czech version of the creative writing workshop coming up. We’re having a first chat with the writer who’ll be running it soon.